Why Constants Break PDEs (and How Poincaré Fixes It)

This post is part of a series which deals with some random topic I had trouble understanding myself during the course of a module at TU Berlin. I hope that writing about it will further clarify the topic for myself — and perhaps be useful to others as well.

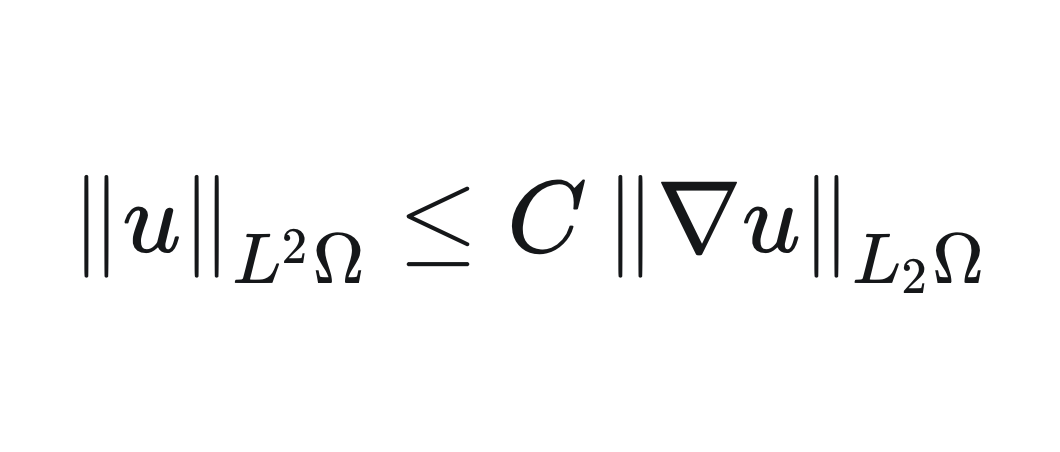

So today we talk about the Poincaré inequality and its use in PDE theory. I begin by stating that inequality without proving it - as neither did Prof. Breiten in the Numerical Mathematics II for Engineers module at TU Berlin — and it is not necessary in order to apply it.

\[ \left\|u\right\|_{L^2{\Omega}} \leq C \left\|\nabla u\right\|_{L _2{\Omega}} \]

In Finite Element Methods (FEM) we are working with this inequality in order to prove the so called "Coercivity" which is ultimately important to ensure uniqueness of solutions in the realm of Poisson equations, which is a PDE i give here below:

\[ - \Delta u(x) = f(x) \]

Now in FEM we like to work with base functions in a so called Hilbert space, which I will not explain in more detail here. Suffice it to say that we like our base functions to live in the Hilbert space \( H^1_0 (\Omega)\) which allows for every function to be one time differentiable (upper index) and being zero at the boundary of our domain (lower index).

Poincaré just works in this specific \( H^1_0 (\Omega)\) space it does not work in \( H^1 (\Omega)\) which allows functions to be non-zero at the boundary of the domain \( \Omega \). So why is that ?

To answer this we need to introduce one more thing. The norm of the \( H^1 (\Omega)\) space. This norm is also valid for \( H^1_0 \in (\Omega)\) as this is just a smaller, thus restricted function space living inside of \( H^1 \in (\Omega)\). The norm is as follows:

\[ \left\|u\right\|^2_{H^1{\Omega}} = \left\|u\right\| ^2_{L^ 2{\Omega}} + \left\| \nabla u\right\| ^2_{L^ 2{\Omega}} \]

I know — at this point the mathematicians are smiling, while everyone else might feel the headache starting. Bear with me for a moment. A simple example will make this much clearer.

Let's assume we have a very simple, constant function \( u(x) = 5 \). The derivative of that function is zero. Now what does this mean for our \( H^1 (\Omega)\) norm ?

\[ \left\|5\right\|_{H^1{\Omega}} = \left\|5\right\|_{L^ 2{\Omega}} + \underbrace{\left\| \nabla u(x) \right\|_{L^ 2{\Omega}} } _{=0} \]

Now what happens to Poincaré if we plug this in ?

\[ \left\|5\right\|_{L^2{\Omega}} \leq C \underbrace{\left\| \nabla u(x) \right\|_{L^ 2{\Omega}} } _{=0} = 0 \\ \left\|5\right\|_{L^2{\Omega}} \leq 0 \]

This is obviously wrong ! What happened ?

This shows that the Poincaré inequality does not hold on \( H^1 (\Omega)\) in general. The reason for this is, that gradient vanishes for constant functions (like our \( u(x) = 5 \) ) which breaks the inequality. So, in order to avoid this problem we need to operate in the \( H^1_0 (\Omega)\) space which allows only \( 0 \) as a constant function. For a constant \( 0 \) the inequality would hold: \( 0 \leq 0 \).

So now, we chose such a function \( u(x) \in H^1_0 (\Omega) \) , a Sobolev space of functions that vanish on the boundary. We insert it in the \( H^1 (\Omega)\) norm and the squared Poincaré inequality, we can make an important deduction :

\[ \begin{split}\left\|u\right\|^2_{H^1{\Omega}} &= \left\|u\right\| ^2_{L^ 2{\Omega}} + \left\| \nabla u\right\| ^2_{L^ 2{\Omega}} \\ \left\|u\right\| ^2_{L^2{\Omega}} &\leq C ^2 \left\|\nabla u\right\| ^2_{L _2{\Omega}}\end{split}\]

Now we insert he inequality into the norm definition:

\[ \begin{split} \left\|u\right\|^2_{H^1{\Omega}} &= \left\|u\right\| ^2_{L^ 2{\Omega}} + \left\| \nabla u\right\| ^2_{L^ 2{\Omega}} \leq C ^2 \left\|\nabla u\right\| ^2_{L _2{\Omega}} + \left\|\nabla u\right\| ^2_{L _2{\Omega}} \end{split}\]

We simplify the right hand side and get:

\[ \begin{split} \left\|u\right\| ^2_{H^1{\Omega}} \leq (C ^2+1) \left\|\nabla u\right\| ^2_{L _2{\Omega}} \end{split}\]

From this we can already say: Well, up to a constant our norm \( \left\|u\right\| _{H ^1{\Omega}} \) is the same as our gradient norm \( \left\|\nabla u\right\| _{L _2{\Omega}} \). We can finally rearrange this a bit and introduce a new variable called \( \beta = \frac{1}{C^2 +1}\)

\[ \begin{split} \frac{1}{C^2 +1} \left\|u\right\| ^2_{H^1{\Omega}} &\leq \left\|\nabla u\right\| ^2_{L _2{\Omega}} \\ \\ \left\|\nabla u\right\| ^2_{L _2{\Omega}} &\geq \beta \left\|u\right\| ^2_{H ^1{\Omega}} \end{split}\]

The gradient \( \left\|\nabla u\right\| ^2_{L _2{\Omega}} \) defines only a seminorm in \( H ^1 {\Omega} \). On \( H_0 ^1 (\Omega)\) however, Poincaré shows that this seminorm becomes a true norm, and it is equivalent to the usual \( H ^1 \) -norm:

\[ \begin{split} \left\|u\right\| _{H _0 ^1{\Omega}} := \left\|\nabla u\right\| _{L _2{\Omega}} \end{split}\]

Now we have an expression that gives the gradient norm a lower bound in terms of the \( H^1 \)-norm. Returning to the Poisson equation and its associated bilinear form,

\[ a (u,u) = \int_{\Omega} |\nabla u| ^2 dx = \left\|\nabla u\right\| ^2_{L_2{\Omega}} = \left\|u\right\| ^2 _{H _0 ^1{\Omega}} \geq \beta \left\|u\right\| ^2_{H ^1{\Omega}} \]

we see that the energy of the Poisson problem depends only on the gradient. By choosing the space \( H^1_0 (\Omega)\) , Poincaré ensures that this energy controls the full size of the function.

This domination property is precisely what is needed for coercivity. It guarantees uniqueness and stability of the solution via the Lax–Milgram theorem. Without Poincaré, constants would survive in the space, the bilinear form would fail to dominate the norm, and the energy would no longer control the solution.